ISLANDS – triptych / light installation in public space

Islands were created as part of „imPark“ in the Munich Olympiapark – a public exhibition, that evaluates the culture and history in multi-medial way. Smigla-Bobinski developed a work in three parts for the Olympia Lake in the very centre of the park, that is not conceivable with just one glance.

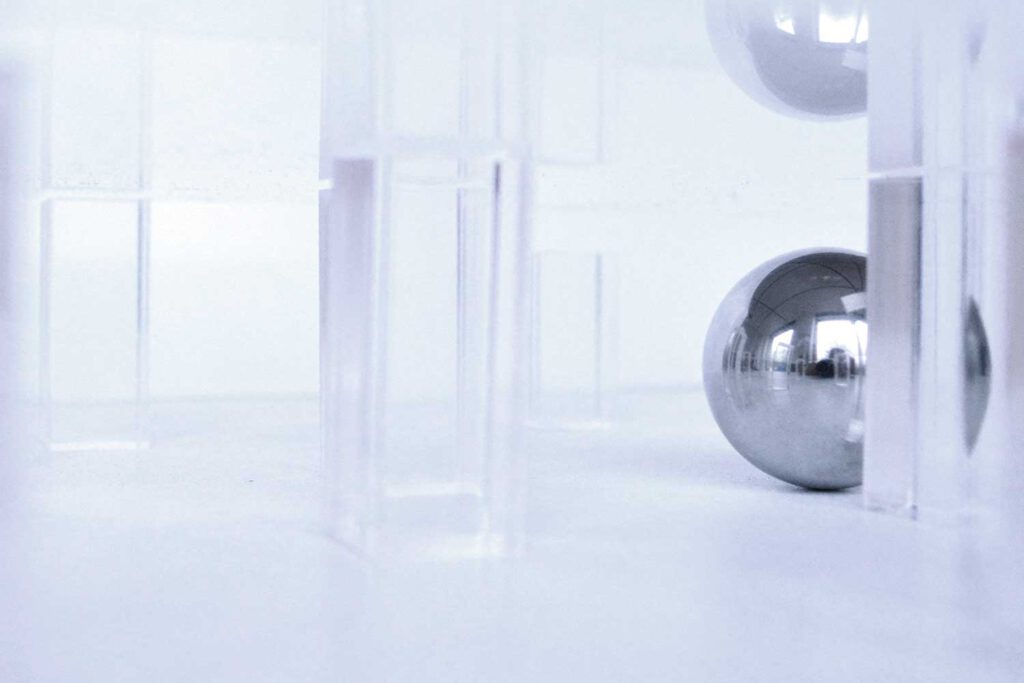

In daylight three grass islands floating above the surface of the lake looked as they always belonged there. The structure transferred the morphology of the park, with its soft curved hills, into a strange element. In the evening the little island hills began to disappear and naked women appeared under them, rolled up in sleep. Their life sized images glimmering strangely in the water quote the stories of Rubble Women (Trümmerfrauen), who allegedly removed the debris of destroyed cities after the Second World War. However, this is a mirage, similar to the reflections in the water. A media campaign created the myth in post-war Berlin, which since the 1980s stands for an entire generation. In fact, however, the highest hill in the park, just next to the lake, consist of the debris of bombed Munich and was called simply ‚Schuttberg‘ (meaning: debris hill). Staging the Olympic Games at this site and remodelling the urban periphery had an important symbolic political relevance. Smigla-Bobinski combined the two leitmotivs of the epochs: the architecture of the park, its flowing curves and round features, as a statement against the fascistic celebration of the central axis, as well as the fictional story of women heaping up the hill from the rubble left behind. The artist thereby lays open the whole nature of this place.

The islands with the reflections of the sleeping women release the story trapped inside. How important are stories and legends for a nation? When does a story become dangerous propaganda and when it does become a useful tool?

In a different way, but nevertheless the artist too, she makes use of these figures to create an optical illusion. She uses the static images of sleeping women and bring them into life. Usually an illusion of fluid movement is achieved by 24 frames per second. Smigla-Bobinski, however, uses only 1 image and lets the water produce the remaining animation frames.

Furthermore, with the representation of the nude body the artist opens up another associative space: the hidden and subliminal – but also the universal allegory of nature, which is cultivated and civilised in parks, while lying dormant under the lovely surface.

© Dr. Thomas R. Huber, 2013

ART CONNECTIONS

OTHER WORDS

> Web version on www.porta-polonica.de

Halfway through her painting course Karina Smigla-Bobinski gave up the two-dimensional media in order to experiment with light and video installations. From then on space has been her favourite place in which to realise her art. She recognises the great potential of an active audience and thus designs the places where she works into collective spaces for active and creative participants. She regards her art as a medium of communication. Her works are materialised events springing from her observations and thoughts in the border area between art, science and philosophy. Karina Smigla-Bobinski lives in Munich. Anyone who wants to contact her will be more likely to meet her at one of the many art festivals in one of the forty countries and five continents in which her works are shown.

Karina Smigla-Bobinski was born in Stettin in 1967, and between 1986 and 87 she studied at the Academy of Pictorial Arts in Kraków. In 1993 she continued her studies at the Munich Academy as a master student under Gerhard Berger, which she completed with a diploma.She invited the general public to participate in her work as early as 1999 in her installation entitled SILVER SALT. When visitors enter the space which is completely covered in earth, their footsteps uncover mementos like photographs, locks of hair, ribbons and letters placed under plexiglass plates. Each visitor uncovers another piece of history for, according to Marcel Proust, the past hides itself “as soon as it has passed away, within a material object“ and not in the memory created in our minds (Contre Sainte-Beuve, 1954). The title of the installation refers to the materialisation of the past through the light-sensitive substances used in photography. The installation changes just as the stories change with every revealed memento. “A work of art no longer belongs to you once you have released it. Then it is a part of the world, influences it, and changes the world and itself through the confrontation with other people.” (Karina Smigla-Bobinski)Karina Smigla-Bobinski was born in Stettin in 1967, and between 1986 and 87 she studied at the Academy of Pictorial Arts in Kraków. In 1993 she continued her studies at the Munich Academy as a master student under Gerhard Berger, which she completed with a diploma.

She invited the general public to participate in her work as early as 1999 in her installation entitled SILVER SALT. When visitors enter the space which is completely covered in earth, their footsteps uncover mementos like photographs, locks of hair, ribbons and letters placed under plexiglass plates. Each visitor uncovers another piece of history for, according to Marcel Proust, the past hides itself “as soon as it has passed away, within a material object“ and not in the memory created in our minds (Contre Sainte-Beuve, 1954). The title of the installation refers to the materialisation of the past through the light-sensitive substances used in photography. The installation changes just as the stories change with every revealed memento. “A work of art no longer belongs to you once you have released it. Then it is a part of the world, influences it, and changes the world and itself through the confrontation with other people.” (Karina Smigla-Bobinski)

Karina Smigla-Bobinski’s early videos are also about the way we perceive human existence. In a break with conventional habits of seeing she installed the monitor for the video EMERGING in a recess in the floor so that visitors were permanently able to look down on a person emerging from the water in an endless loop. The video DREAM JOURNEY is a surreal journey into a world roughly the same size as a human life. “When people ask us who we are, we tell them stories about us”, explained Laurie Anderson when she was talking about her album Album Bright Red (1994), whose songs are responsible for the musical part. The video is a sequence of memory fragments and emotional states in the form of abstract poetic sequences in which the hands of two lovers touch each other and remove themselves once more, coloured drops of water fall into a watery surface, float past each other, come together to make up a duet and finally dissolve into blurry streaks. Photos of a little girl function as testimonies to the memory of her being swept away on a journey by her father. The sea horizon, reflections in the water and the movement of the waves underline the permanent fluidity of life and a life lived between dream and reality.

A whole presence of a person with his/her forms of interaction, strengths and weaknesses, also stands at the centre of the video ROUTES. A face made up of drops of water simultaneously emerging, distorting and flowing into one another is looking more inside itself than at the viewer: it symbolises isolation and the fruitless nature of passing life. Its different states make it a metaphor for the plurality inherent in individuals and all the different roles in a person’s daily life. Karina Smigla-Bobinski not only thematises aspects of a philosophy of being but, by using the artistic techniques of video and other different forms of presentation, involves her viewers in a discussion about people’s social status.

The role of individuals over and against other people is thematised in the interactive video installation ALIAS. Here visitors stand in front of running projectors to throw a shadow on a white wall: within the white wall can be seen life-size video projections of other people, mostly of other origins and nationality. Just as in Plato’s “parable of the cave” the projection surface becomes an object of discussion about one’s own reality, whereas the projections of the visitors’ shadows throw up questions about their relationship to other people.

The techniques of the artist are just as ephemeral as the expressions of life they document: video and slide projections are as ephemeral as the places in which they take place: images for performances on stage and situations created in public spaces. In 2000 she began work on a video set for a dance performance entitled SEE AND BE SCENE – A CATWALK BANQUET, that was created over a number of years. The show was directed by Helena Waldmann and based on motifs from the novel “Glamorama” by Bret Easton Ellis. Here three female Japanese dancers play out a drama of vanities on a catwalk. Karina Smigla-Bobinski projects their faces, mirrored in drops of water, on a screen hanging 6 metres above the stage. The performers wait for the drops of water to explode with the “horrified expression of prisoners shortly before their execution”, until the drop of water dissolves itself into a trickle. Once again the viewers are involved for they can only see the projection with the help of mirrors.

Karina Smigla-Bobinski also stages metaphors of memory in public spaces. In 2004 she installed three grass covered artificial ISLANDS in the lake of the Munich Olympic Park near the Olympia Hill, beneath which the rubble from the destroyed city was piled up after the Second World War (it has now been greened over). At sunset reflections of light revealed women sleeping in the depths: they could be interpreted as personifications beneath the park containing hidden memories of the war. The artist intended the natural movement of the water to create the impression of a video in which the women could be seen breathing and moving gently. Her work with video techniques originally goes back to her paintings studies at the Munich Academy, during which she engaged with the theory of colours and form, and finally with light and space. The reflections in the depths of the lake not only paraphrased the transformation of individual images in a film turned into motion by nature; the sleeping female figures could also be interpreted, as in classic paintings, as allegories of nature or of the women who worked so hard to reconstruct the city (Thomas Huber, 2014). In 2008, the artist used a similar projection entitled DEEP TREE on the occasion of the sculptural project Ciudad de la Escultura (City of Sculpture) in Mérida in the Mexican state of Yucatán. Here she installed a network of living bamboo canes corresponding to tropical vegetation. The work threw up associations with the mythological Earth Mother Pachamama, who is admired by the indigenous peoples of South America because she gives them life, nourishes them and protects them, is capable of ritual communication and today symbolises identity, social and political resistance, and the hope of an all-round structured life.

Whereas SEE AND BE SCENE (2000) and ISLANDS (2004) implied social, critical, historical and political aspects, the projects between 2005 and 2009 were expressly motivated by social and political considerations. Sensing in advance the dramatic development of refugee problems she was treating the sealing of the outside borders of “Fortress Europe” as early as 2005. Here she reacted to the extension of the border fence around the Spanish enclaves Ceuta and Melilla with her room installation 7 METRES, in which chain-linked fences and barbed wire fences prevented visitors from moving freely within the gallery.

The dance theatre show LETTERS FROM TENTLAND (2005 in Teheran) caused a political uproar. Here the director Helena Waldmann visualised the lives of the Iranian women caught between veils (symbolised by life-size tents) and liberation (symbolised by spoken letters to correspondents abroad). Karina Smigla-Bobinski was responsible for the stage projections featuring images and film sequences from everyday life in Iran. The production was shown in seventeen countries around the world. When a shift in power prevented the Persian protagonists from travelling abroad any more the production was moved to the West with a counter-title RETURN TO SENDER. Now exiled Iranians women from Berlin are living in the tents that have become a symbol of provisional housing: the letters spoken in Iran are passionate pleas for freedom. Alongside music, the video projections by Karina Smigla-Bobinski play a major role. She brings the Iranian world onto the stage with her stills and film sequences of family members of the dancers, urban panoramas of Teheran and lines in Persian writing.

Karina Smigla-Bobinski demonstrated her sense for dramatic and controversial developments once again in her multipart art project QUERY presented around St Luke’s Church in Munich. The project asked critical questions about the meaning of religions and their place in our lives […] Do we really still need places of worship like churches, mosques and temples?” The installation of a balloon with a printed question mark orientated on the form and colours of markings on Google Maps simultaneously put the church on the worldwide net and questioned its validity. An internet project offered users the opportunity to go online to express their own standpoints with regard to the questions put. QUERY thematised the split between people’s religious attitudes and global management and the role of the internet as an information platform that has been dictating the attitudes of the world for many years now. Karina Smigla-Bobinski is of the opinion that the fierce (and ever increasing) religious conflicts between Moslems, Jews and Christians completely contradict the globalisation on the World Wide Web that challenges the right of religions to rule the world. In 2008 she showed another work dealing with globalisation at the Biennale in Busan. The video installation, entitled WORMHOLE, showed two places at opposite ends of the Earth (Busan and New York) by means of a fictional direct visual link through a hole in the ground. Here people beneath the skyscrapers and skies above New York could peer through a wormhole down onto Busan. Thus modern technology was able to bring the world closer together.

The artist’s current works are closely linked to the development and understanding of state-of-the art technologies. In 2011 she created ADA, a writing machine in a white room consisting of a spherical outer skin filled with helium with pieces of charcoal on the outside. Visitors were asked to hit them, upon which they began to make quasi-spontaneous drawings on the ground, ceiling and walls. The work can still be seen in exhibitions and art festivals around the world. ADA is a reference to Ada Lovelace (1815-1852), a British mathematician and the daughter of Lord Byron, who laid down the basis for a mechanical computers to produce works of art. Thus it was also intended to work independently and develop something like its own personality. At the same time visitors were encouraged to involve themselves in an interaction: not simply to observe the work of art but also to intervene in the production process. The machine was dependent on how violently it was moved, but could only be controlled to a certain extent. The resulting drawings resembled nanostructures configured by nanoswitches in state-of-the art computer processors, that are also responsible for links in the human brain.

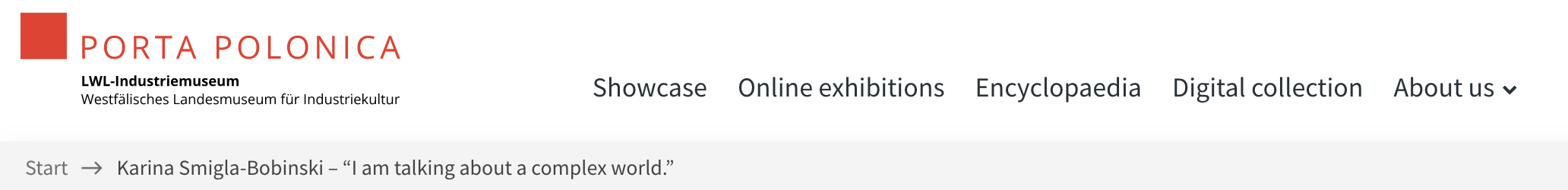

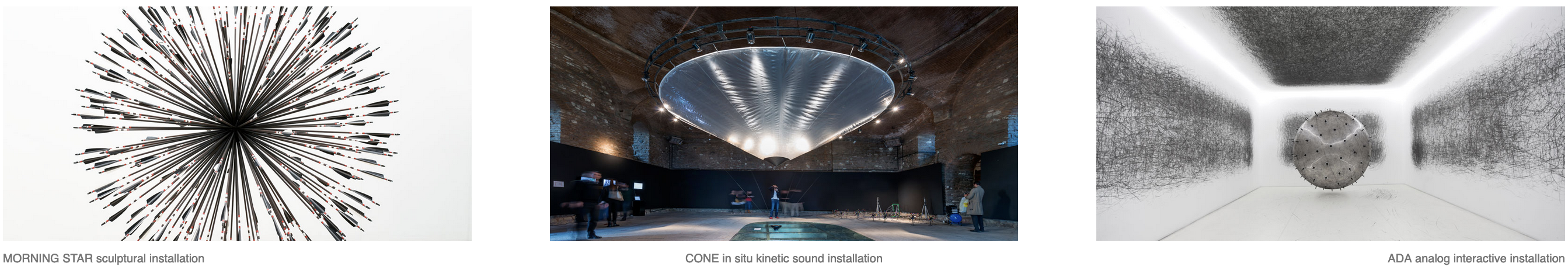

Karina Smigla-Bobinski’s “bridge between media technology and the psychology of perception” (Thomas Huber, 2014) was clear in her experimental setting SIMULACRA, that was shown for the first time in 2013 in the Museum of Transitory Art (MoTA) in Ljubljana. A cube made up of four white LCD screens with visible cables and control units initially seems like a conspicuous source of light. But with the help of visitors it can be brought to life with the help of magnifying glasses. These contain polarisation foils that have been previously removed from the screens, and which reveal the film running on the video screens once more. The body parts, hair and touching hands and feet seen on the film on the inside of the screen suggest that human beings are inside the apparatus. The general public is not only encouraged to try out new ways of seeing, for turning the magnifying glasses in different ways results in ever-changing optical effects. On the basis of debates that have been conducted since the 1980s on the flood of images in contemporary life, the apparatus also helps us to realise that, in an age of globally mediated electronic images, our image of reality is not created within machines but inside our heads. This is also similarly applicable to auditory experiences, as was shown in the same year by Karina Smigla-Bobinski in her sound installation CONE beneath the cupola of the historic Tophane-i Amire Culture and Arts Centre in Istanbul. Water that seems to be dripping continuously into the building through an opening in the vault is in reality coming from a loudspeaker over the film cone installed in the space above.

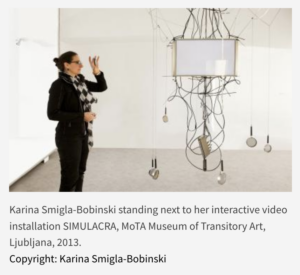

MORNING STAR, 2013 developed for the international exhibition “gast.freund.schaft – sculpture Europe” in Trier is surprising for its precise construction: the spherical sculpture consists of hundreds of arrows surrounding the “black hole” in a field of gravitation in the centre. The “shafts” (a pun on part of the German title) of the arrows link the deadly tips on one end of the arrow with the soft feathers on the other, two aspects of hospitality (“Gast.freund.schaft”“= guest.friend.ship or hospitality), that might be experienced in various attitudes both at home and abroad. The title of the work is equally ambivalent: it is not only another name for the planet Venus but was also a deadly war weapon in the Middle Ages.

The selection of works displayed here show that Karina Smigla-Bobinski is not fixed to any particular art form. Alongside classical room installations, she works with videos, stage shows, in specific situations and different places, with internet projects, installations in public spaces, and sound, not forgetting electronic and kinetic experiments. For her, technological and philosophical frames of reference are not ends in themselves but general means to present themes in an artistic manner. In 2013 she spoke about this in an interview with Ida Hirsenfelder: “For me the technical solutions are never only formal. […] When I use technical things, I like to use them in a very clear way. I need to use a simple language, because I am talking about a complex world.”

Since 2005 she has been teaching and giving guest lectures and workshops in universities and cultural organisations around the world. Since 2013 she has been a member of DiBari Innovation Design in Florida (USA), a design studio, in which architects, artists and designers can work together on visions of future cities. At the end of 2015 she will work as Artist in Residence in the centre for interdisciplinary research at the University of Bielefeld, where she will cooperate with academics from different disciplines all over the world to research the “ethics of copying” and the” genetic and social causes of life opportunities”. The results will be shown in an exhibition.

Axel Feuß

* *** *

When the world in magnified – Discussion with Karina Smigla-Bobinski

by Ida Hirsenfelder > MoTA, Museum of Transitory Art in Ljubljana

Perhaps it would not be fair to say that the following discussion – taking place during Sonica Festival 2013 at the end of Karina Smigla-Bobinski’s artistic residence at MoTA, Museum of Transitory Art in Ljubljana – is an interview. It would be far more accurate to call it a transcription of storytelling by the artist herself. Most importantly and most decisive for her artistic processes, narratives and contents, mediums and techniques, as I came to understand, is her overwhelming passion for art which is taking her to places she has never imagined, always embarrassing new experiences and manifestations of beauty, revealing paradoxes of society with artistic language with the gaze of a child and the brain of a mathematician.

Ida Hirsenfelder: You are an artist with a long and versatile career. It is quite interesting for me, that you started using video and making video installations despite the fact that this technologies were quite unavailable in Poland in the 80s. The artists who at the time thought about video processes were mostly using film in a videastic manner. How did you start?

Karina Smigla-Bobinski: When I was in elementary school, my father had an double 8 mm Russian film camera and he was very fascinated with making films. At that time it has really never occurred to me that one day I will be an artist working with this kind of medium. Nevertheless, this was an extremely important experience. The double 8 mm camera tape had a really peculiar characteristic. After shooting for few minutes, the tape needed to be turned around in the dark room, so images could be recorded on the flip side of the tape. So my father actually used a scarf to cover the film and flipped it. What I still find very curious is that he was not making family portraits or films of people, but taking long and quite abstract footages of cars and time passing by.

IH: Do you still have the tapes? Did you ever exhibit them?

KSB: Yes, I still have the tapes. I never exhibited them, but I might do this one day. It is not yet the right moment. And you know I also have his camera that he gave me, when I was still only painting.

IH: Until when did you only paint?

KSB: Until the middle of my studies in Munich actually. It was strange how I came to art. As I was little, I was mostly good in natural sciences in physics and mathematics, only when a teacher showed us a Malevich painting, something moved in me. Much later when I was already at the academy in Munich, I set myself a research about painting. I asked myself a question: What exactly is painting? Painting is colour and form. I examined both of them, but the world of colors really fascinated me. And hence I came to exploring the qualities of light and space. This discovery also brought me to light installations and to video.

IH: Are you still connected to the Polish art circles?

KSB: I am starting to establish the communication once again, now. After over ten years of living abroad in Munich, I was back to Poland, when I was invited to install an exhibition in Krakow.

IH: In the past few years, I saw a number of installations like “Morning Star”, “Cone”, “Ada” in the context of media art exhibitions. Before this pieces, you were maining light installations, a lot of video installations and also some intense work on theatre scenography. Are you still making theatre or are you completely dedicated to media art now?

KSB: After working in the theatre for a number of years I was doubtful whether I can still make art by myself in my studio. This mood overwhelmed me out of several reasons. The theatre piece was very important, informative, and we got to travel with it all around the world. Each time the performance would stop, we would get an enthusiastic applause and appraisal, people saying how beautiful it was. But when the piece is made, after the first premier and a few reprisals, you yourself as an artist do not have to do anything creative anymore. You start to enjoy the applause and start to feel far too comfortable with rewarding situation. This triggered an alarm in me. I though, I have to keep my focus on the work and specifically on the work alone. At the certain point in 2008, I decided to quit the theatre collaboration in order to develop my own artistic language.

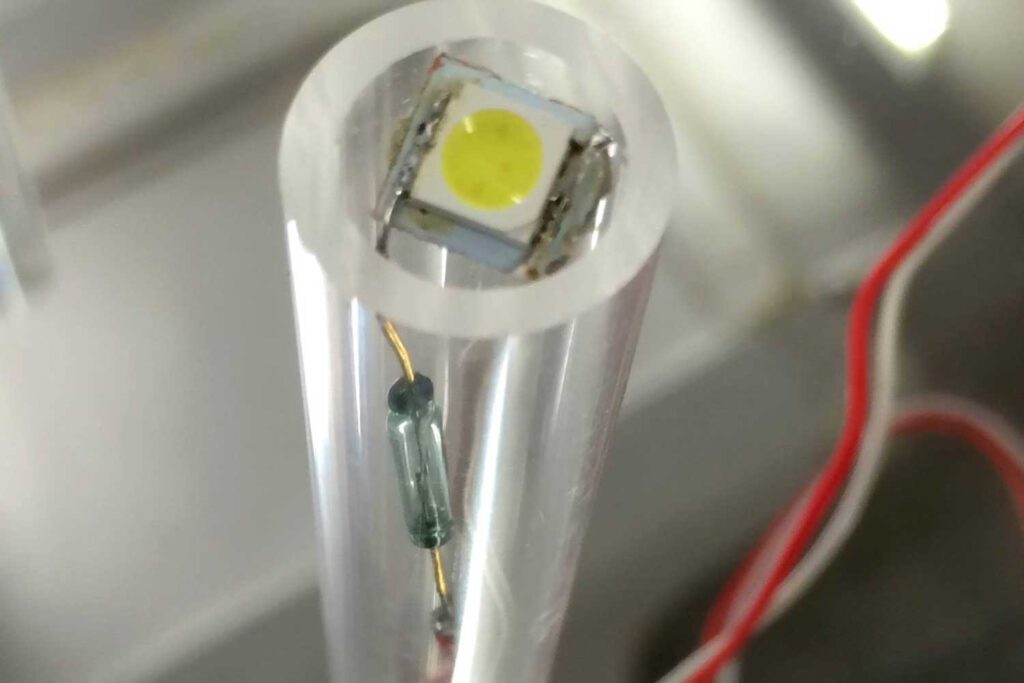

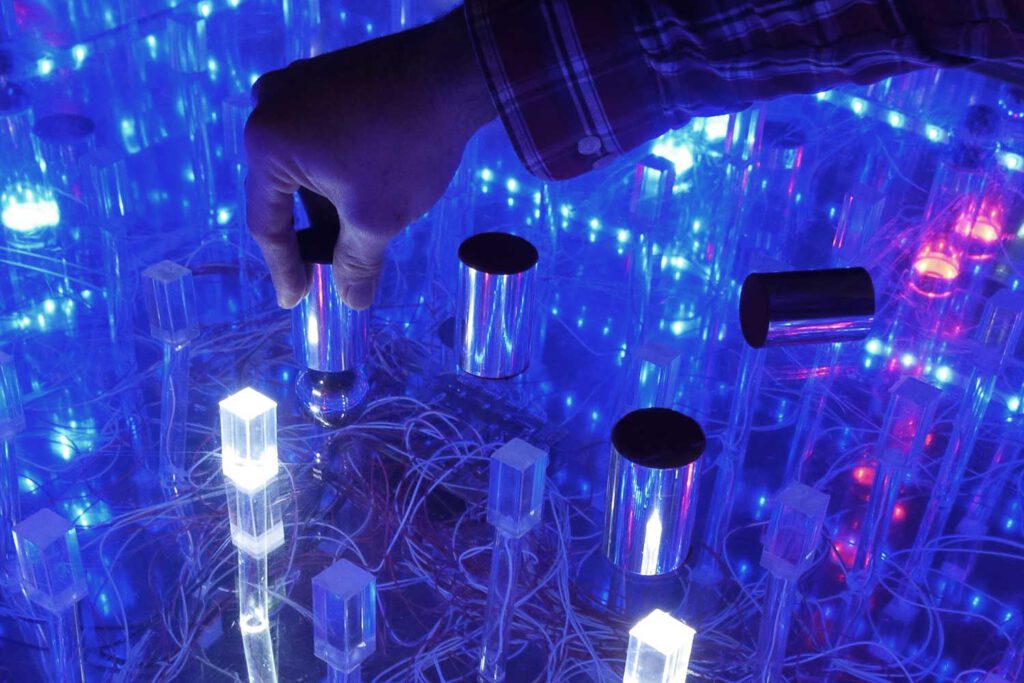

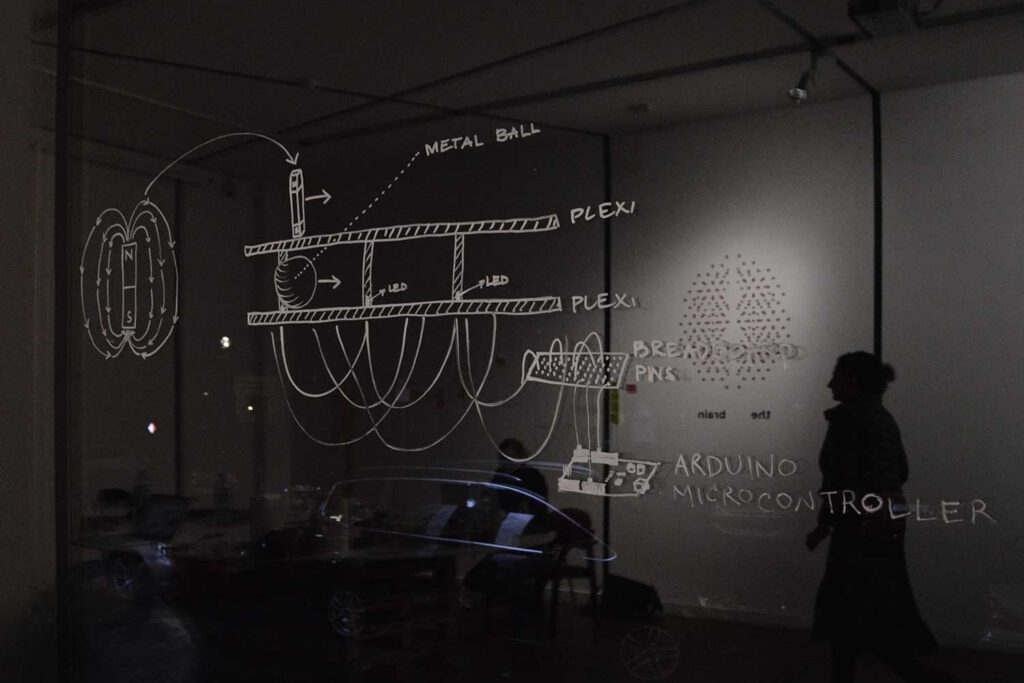

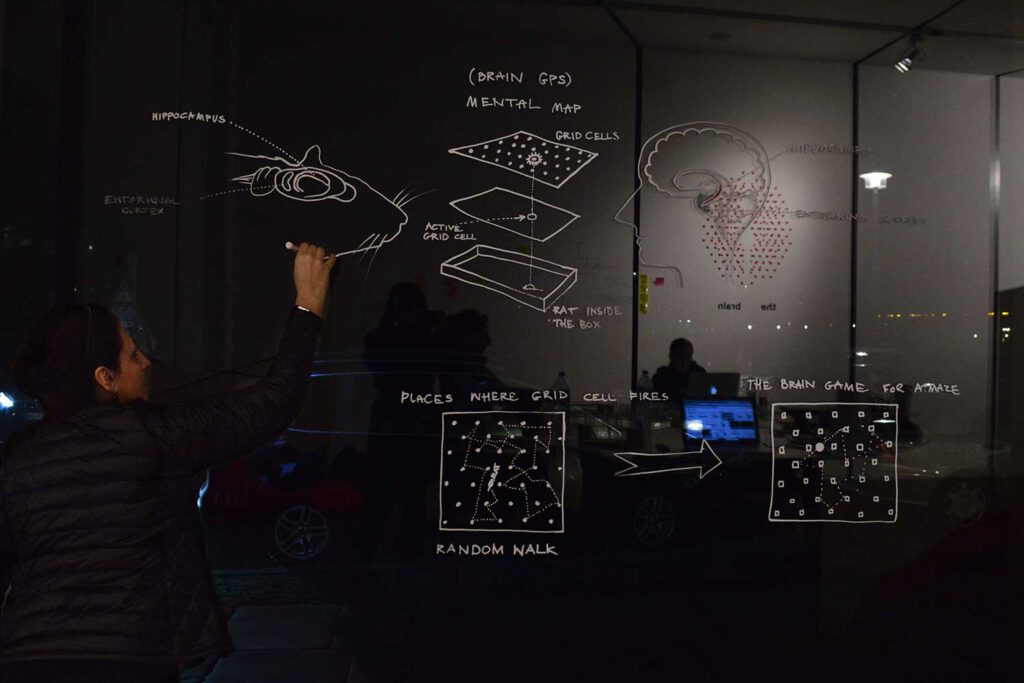

IH: Like a repressed traumatic memory.

KSB: I was wondering what would have happened if I was to cut this hill at its foot, place it on the water and make water reflect what is hidden inside. I installed hill-like shaped islands in the middle of a large pond seemingly floating on the water. I covered them with grass and they looked very natural to a casual observer. No one had thought that this was an art piece during the day, but during the night one could see a reflection of sleeping naked woman in the water. For the piece, I only used a large diapositiva on each of the islands and plexi glass that was placed at the bottom of this floating islands. This was not a projection on the water, because this is physically not possible. It was a reflection and thus gave an optical illusion that the women are deep in the water.

IH: Conceptually it also makes a lot of sense to reflect the historical memory and not to project it.

KSB: Yes but also the idea of video itself. In any of my installations video was never just use as a moving image. When the body of a dancer or the surface of the water was moving, I would rather use a still frame than a moving image. In the case of “Islands” I only used a single dia image and then let the water became a generator of movement and produce the other 23 frames. The water made the sleeping body look like it was breathing.

IH: Very often, you would also address hidden political or social agenda in your work, at the same time your installations came off as very formally clean, also monumental in a way. You also often work with large scale. What reasons are behind your decision to produce monumental and formal and seemingly formalistic works, and how does this correspond the social questions that you are addressing. In “Ada” you also used scientific and neurological explanations…

KSB: This all depends on what I want to communicate to the people. I search for form, which is very present, which the people can comprehend, feel immediately and I think there is a better way to communicate. I believe, when you have a very strong emotion, you need to have something very subtle to mediate it. Or even better, you cannot say anything about the light without the shadow. In the aesthetic sense this comes out as something clean. That is how I work with the installations. Another example would be mysticism. I know that in our society there is a lot of interest in getting in contact with spirituality, but a lot of people make a huge mistake, when they are over-emphasising it and they start to be esoteric, they fail to recognise the importance of the material world. … I like to speak about polarities.

IH: Another very intriguing layer of our work is your approach to new technologies. You often produce a piece, which would not be possible without computers and laboratories, but you do not directly use computers. In fact, you even cal “Ada” an analogue interactive installation. You used a similar principle in “Morning Star” in which you built a rhizomatic structure with arrows. There was no new technologies only new vision of the physical.

KSB: I want to address people’s fear about the digital. I dislike the paranoid approach to the digital world that suggest that it takes our reality away from us and that we become less alive when using them and somehow become lost in the virtual space. Come on! A century ago with film and photography a lot of people were saying that that will be the end of painting, the end of culture. Why are we afraid of new technologies? The question is not technology in itself, the problem is how we use it. One thing is for sure, it is very wrong to be afraid of it. I wanted to take the fear out of the people and to prove that understanding the digital is simply exploring my understanding of the world.

IH: It is interesting how a lot of artists were working with virtual reality at the beginning of 2000, but now no one talks about virtual reality and real reality because we constantly live it, it is not something separated anymore.

KSB: The idea of fractals by Benoit Mandelbrot was first a mathematical question. If we can make a shape, can it be endless? Yes. It is not such a complex procedure. You have a line, you cut it in half the middle, you cut it again in half and again and again and this story never ends. You get deeper and deeper. It seems absurd, but it is the beginning of the virtual. You may only imagine this shape existing in our head, it does not happen in the physical reality, but it tells everything about the way we see the world now.

IH: It is interesting how through the history of art and also through your own artistic history we came from abstract art to infinite art. Virtuality basically is the possibility to think in the infinitum in the same sense we may thinking of the universe as an endless expansion until we cannot think about it anymore, but it still continues. It is really interesting how you play with this notion of virtuality in your latest interactive video installation “Simulacra”. You place a body into a compressed space where the body itself cease to exist. You find a lot of times a very technical solution, yet it is crucial for the content of the work.

KSB: For me the technical solutions are never only formal. You have to understand, when I was a small child, everything for me was living, the chair, the stairs, my puppet. They were not dead. When I started to use mechanical and technical objects in my work, I approached it in the same way as a living matter. That is why it was so important for me to learn about the research of Masakazu Aono, the creator of the first nano-switch, and Argentine neurologist Dante Chialvo who showed that in the nanoscale it does not matter if something seems to be living or something seems to be not living. When I use technical things, I like to use them in a very clear way. I need to use a simple language, because I am talking about a complex world. If I was to use very complex language for complex things we would get lost very quickly in this problem. I use a visual language that people can instinctively work with and they should also feel touched. And I try to prevent that people become afraid of technology.

IH: In “Simulacra” the effect of the polarised screen was very magical or as you say, I felt touched and emotionally addressed by it. Prior to looking through the magnifying glass with the polarised screen I never thought about the physical characteristics of an LCD screen or that only this polarised screen enables the picture to be visible. The stark white empty surface of the LCD without the polarised screen and the image that was visible only through the lense was a new discovery for me and I’m always thrilled to learn something new, but in a sense it was much more important for me, what it actually made me see once I got over the pure fascination. The person in the cube in the video seemed to be in a very claustrophobic place, a very enclosed space, like it would be reaching out of the box and wanting to become physical. In this sense it was very emotional to see this digital person, trapped in the digital world wanting to get out. What this piece also tells me is that the observer finds oneself in an opposite position. We want to become digital and limitless. I see a lot of people who willingly post their intimate stories online through social networks. I think this may be very beautiful not just an act of an exhibitionist. We are trapped in the physical space and we love to be online, on a smartphone, clicking through something far less limited than our physical existence. We love to be in the digital space, it does not just trap us like some technophobes might propose.

KSB: The way I try to do my art is to mediate it directly, so that the public does not need knowledge, does not need to read a long text in order to understand what is happening there. I believe art does not need to be only for intellectuals, but for everybody. I want them to feel immediately addressed. But then it depends on the person viewing, what they are thinking about, what they have read or know or how interested they are to find out. I do not want to push people, so they decide on their own how far and how deep they want to explore what is in front of them. But I do think of all this layers, so I make the installation in the way that it allows for discovery of deeper layers of meanings. One of the key ideas behind “Simulacra” was also the fact that today lot of creativity or fantasy happens on the surface. In this way, connected to the screen, we are already in the matrix. What I wanted to do is to cut this illusion away … like a Red Pill from „Matrix“. Saying, no, that what reaches your eyes, what you see are only different optical light pulses. The process is happening in your brains, it is organic, analogue mental cinema. The claustrophobic figure trapped inside the screen in “Simulacra” is telling us a story of how it already exists in our heads. Hitchcock, one of the best filmmaker worked on this notion of virtuality, showing a shadow, so that the viewer would produce the story and the fear in one’s head. The biggest fear comes from the unknown, from something that has not been lived through yet. You cannot show the feared, you have to stimulate people to produce the fear by themselves … mental cinema. What I did it I removed the fantasy from the surface and placed into the minds. Virtual is what happens in the people’s heads.

…

Ida Hirsenfelder (1977) is a Ljubljana, Slovenia based media art critic and curator for media art. She is a collaborator of +MSUM Museum of Contemporary Art Metelkova for Network Museum online aggregator of contemporary art archives. From 2007 to 2013 she was an archivist at Digital Video Art Archive, DIVA Station, SCCA-Ljubljana. Archives and their disappearance are one of her interests, resulting in lectures dealing with media archeology and the history of Internet. She is also an advocate of free and open source software. From 2010 to 2014 she was a curator at Ljudmila, Ljubljana Art and Science Laboratory. She solders small electronic noise gadgets, driven by the love for machines, electronics, devices and noise/drones as a member of Theremidi Orchestra and collaborates with media artist Sa?a Spa?al on a series of sonoseismic installations produced by Kibla, with Sa?a Spa?al she also co-initiated ? IPke – Initiative for Women with a Sense for Technology, Science and Art. Her fem alter ego Frau Strapatz performs in Image Snatchers techno burlesque.

* *** *

Appearances in a world of appearances

by Cornelia Kleÿboldt, translation Rosmary Romanek

„The sensory impression of colour in humans originates when light of a certain wavelength or mixture of wavelengths falls onto the retina of the eye. Colour is therefore a sensory perception and not a physical characteristic of a body. This sensory perception is activated by „Light that enters the eye and is converted there by specialised sensory cells into a nerve impulse, which for its own part is then transmitted to the brain and which then, in a way not yet quite clarified, enters human consciousness as colour.“ (Definition of colour according to DIN 5033)

Karina Smigla-Bobinski, she regards herself as a painter. However, she has expanded her range of art utensils, which are traditionally allocated for the use of colour on a painting base. Her „art utensils“ can be both colours and light in the form of projected models. Her „painting base“ can be a canvas but also the surface of water, a shadow on the wall, or any other projected bodies with reflective properties. Her „painting techniques“ and „painting tools“ respectively are reflections or projections in which manual interventions or rather operating rules, and especially objects functioning as lenses, take over the transformation of a perceived model into an artistic reality.

As a consequence of her extended understanding of traditional painting, Smigla-Bobinski’s artistic works take place not so much on canvas but more within the framework of spatial installations, utilizing or combining different artistic mediums. Karina Smigla-Bobinski’s artworks can be a matter of space installations or the projected components of a stage setting.

Alongside the application of film or picture projections and object installations, the observer himself can become part of the artistic reality, i.e. the picture, as an active agent or as a participant. At the same time – in addition to his role of observer – he can slip both into the role of the „painting base“ and into the role of the „pigment“, thereby calling awareness to their active characteristics traditionally perceived as passive.

While the precise appearance of the installations repeatedly and flexibly adapts to the specific circumstances of the production or the field of action, it remains obligated, however, to a fundamental idea and/or perception of the artist.

Karina Smigla-Bobinski is less an inventor than an observer. She works like a variable lens, transforming the observed – registered and condensed by the respective characteristics of the lens – from one into the other. As the same time as being an absorbing lens, she also functions as a “painting base” with transforming characteristics. The artist’s role and self-image are not only visible in the conceptual understanding of the work, but they also emerge as transformers and/or recording and projection lenses in her work itself. They are tangible components contained within her artwork, in particular mirroring and/or reflection, as well as the permeability or rather transparency of matter in the form of properties being able to register a picture of the world like a lens, transform it and pass it on further.

It is as if her pictures were „real pictures“ next to or within the so-called „reality“, and ultimately this very coexistence lures one towards illusions. Karina Smigla-Bobinski makes the poetically combined, tapered conversions or rather transformations of her observations and inner recordings appear to look like magic.

The „make-believe“ of her pictures opens views and perspectives on an artistically transformed reality whose possibilities as enrichment and communication prevail next to the reality of the observer. They project reality as assumedly „alienated“ into the area and bring previously unperceived possibilities into play as their representation. It is almost as if an equilibrium between art and reality is created, between an artificial reality and real art with the common denominator being the „appearance“, a visibility totally dependent on light.

The artist dreams dreams and nocturnal truths that withstand the light of day. She creates appearances in a world of appearances. She conjures up her observations, feelings and longings right into the middle of the world, like newly emerging islands that imminently, full of respect for their surroundings and extremely fertile, communicate.

The means are very simple; their effect – the enchantment – seems in contrast all the larger.

The possible role swapping of the components of an artistic work and/or “multiple allocations” increases its complexity and thus eludes a definitive analysis. Ultimately, it is also and above all the observer himself who, once conscious of his adopted observation method, will become an important component of the artworks due to the uniqueness of his manner of observation. In discourse there is always just one way to go; in Smigla-Bobinski’s art, however, one finds a mind-boggling diversity of interlaced interpretation methods.

Dreams are ultimately nothing other than a form of reality: appearances in a world of appearances.

© Cornelia Kleÿboldt, M.A.

Translation: Rosemary Romanek

Munich, 01.07.2005

* *** *

TECHNICAL SPECIFICATIONS

Description > light installation in public space

Components > metal structures, large slides, grass, light, water

Dimensions > 1 island: 2 m diameter

Space > variable, most: 10 m long x 6 m wide x 4 m high

Premiere > 2004, Olympiapark Munich, Germany

Supported by Olympiapark München GmbH